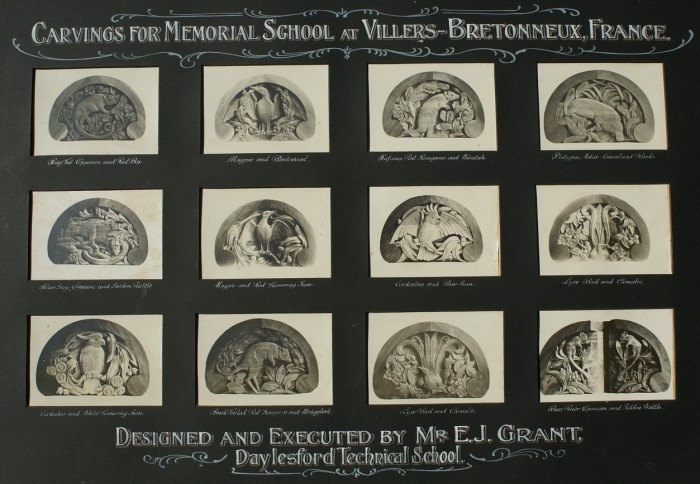

Dans l'école de Villers Bretonneux se situe la salle Victoria avec ses boiseries sculptées par l'artiste australien John Grant et ses étudiants de l'école technique de Daylesford, Victoria, représentant la faune et la flore australiennes. Elle accueille une exposition permanente de photographies sur l'Etat de Victoria offert à l'Anzac Day 2003 par Peter A. Hansen, ancien agent général pour l'état du Victoria à Londres.

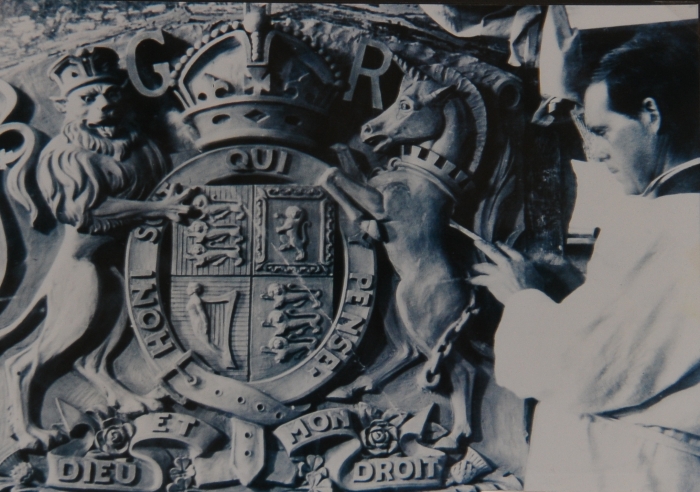

Portrait de John Grant

Dr Lachlan Grant’s office at the Australian War Memorial is filled with books and stories about war, but it’s a copy of an old photograph of 12 intricately-carved wooden panels that stands out.

Designed to adorn the walls of a school hall on the other side of the world, the series of wood carvings of Australian flora and fauna is particularly special to him.

They were carved by his great-grandfather after the First World War in memory of the Australians who died during the liberation of Villers-Bretonneux in France on 24–25 April 1918.

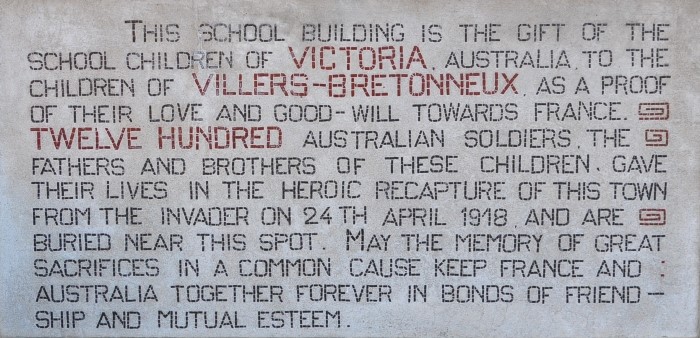

One hundred years after the battle, his great-grandfather’s carvings can still be seen in Villers-Bretonneux at the Victoria School, which was built with funds raised by Victorian school children after the war. Inscribed on the walls of each classroom are the words ‘N’oublions jamais l’Australie’, a message repeated in English on the playground shelter: ‘Do not forget Australia.’

“I had always been told that my great-grandfather had done the wood-carvings that are displayed in the school, but it was only when I got a bit older and started studying history and came to work at the Memorial that I started to realise how significant that legacy has been,” Dr Grant said.

“So many French schoolchildren would have looked upon those carvings since the school was rebuilt in 1927 … and it was quite a special thing for him to be able to leave his mark on the memorials in France and Belgium.”

Dr Grant’s great-grandfather, John Erskine Francis Grant, was the art master at Daylesford Technical School when the Victorian Department of Education asked him in the 1920s to carve a series of relief panels to help decorate the hall at the new memorial school in Villers-Bretonneux.

“Coming on the eve of Anzac Day, it was an iconic battle for the Australians,” Dr Grant said.

“The department gave him some ideas and some plans … but I think he thought they were just a bit plain. He thought, ‘Why don’t I make these panels of Australian flora and fauna to give that nice Australian feel to remember the Australians who served in France and Belgium during the war?’ As it turned out, the department felt that the new designs were much better than the originals, so he was invited to complete a total of 12 pieces.”

Like so many, John Grant had been touched personally by the war.

“I always feel that when he was making the carvings, he must have been thinking about his brother, Harry, who died during the third battle of Ypres in October 1917,” Dr Grant said.

“He was in the Australian engineers, and had served on Gallipoli and at Pozières, and he was in the town of Ypres itself when the engineers were helping to get the water supply going … and clearing the rubble from the damage from all the shelling. One night a shell hit the billet that the engineers were staying in, and he was one of the 11 who were killed. That was on the 27th of October, and he’s buried in the town of Ypres in the Menin Gate South Cemetery.

“My great-grandfather also lost one of his close friends, Joseph Pooley, who died from wounds received in France, as well as a brother-in-law, Stanley Waters, who died at the battle of Krithia on Gallipoli in 1915. He also had several cousins who served, some of whom died as well, so I always think, he must have been thinking of them as he was doing the carvings.”

Today, Dr Grant is in Villers-Bretonneux for the 100th anniversary of the battle with the winners of this year’s Simpson Prize, a national competition for high school students which encourages participants to explore the significance of the Anzac experience and what it means for Australia.

“To be in Villers-Bretonneux on Anzac Day, and to be able to visit the school, and to be able to stand in the school hall, and to be able to share that story with a group of students and the next generation of historians … is quite a special thing for me,” Dr Grant said.

“One of the things that sinks home when you visit the battlefields is that so many young Australians – a lot of them only a few years older than the students themselves – were so far from home when they were involved in such a large and horrendous event.

“It’s quite a special trip, and quite an emotional trip too, reflecting on what it must have been like for those who died and for those who endured and survived the experience of life in the trenches and the terrible nature of combat on the Western Front.”

Made with Pacific maple, the panels at the Victoria School were created by John Grant during his spare time, and each took about a month to complete. “Some of his students helped him with the carvings, and it’s said that his students have written their names in the back of them,” Dr Grant said. “We can’t be certain about that, but that’s the story … and Thomas Trengrove, an instructor at the Ballarat School of Mines, created a further four panels.”

After the war, Dr Grant’s great-grandfather continued teaching in Daylesford until his retirement and ran a guesthouse with his wife Lily. Visitors included well-known members of the Australian art community, including artist Tom Roberts, and one of Grant's students, Stanley Hammond, went on to become a well-known sculptor whose works decorate the parks, buildings and public spaces in Melbourne and Sydney.

“Like my great-grandfather, he has left his mark on the memorial landscape in France as well,” Dr Grant said. “He sculpted the digger for the 2nd Australian Division memorial at Mont St Quentin. It replaced the original by C. Web Gilbert which the Germans destroyed during the occupation of France in the Second World War.”

Dr Grant said the memorials were a lasting reminder of the bonds forged between communities in Australia and France, and his great-grandfather would have been honoured to have been given the opportunity to make a small contribution.

“On a personal level, his works were no doubt a fitting memorial to his own family and friends who did not survive the war,” he said. “As with many families across Australia, these losses were a cause of strain and lasting grief. It must also have been very stressful for John and his wife, Lily, when war broke out in 1939 and each of their three sons rushed off to enlist.”

It was this family history, and a visit to the Australian War Memorial at the age of seven, that also helped shape Dr Grant’s own career choice.

“My grandfather, who is also named John Grant, served during the Second World War in the Middle East and New Guinea, and at Balikpapan. He would talk about the war years quite a lot, and my mum’s father also served in New Guinea during the war. He would tell stories to my brother and me that my mum and her brother had never heard before. I think that knowing those stories about my grandparents, and then later on about my great-grandparents’ generation, did very much shape my choice to become an historian.

“The last my great-grandfather would have seen of the panels was packaging them up in Daylesford. They didn’t have that luxury that we have today, where it’s very easy for us to get around; but his eldest daughter, who was still alive until a few years ago, remembered seeing them being packed up and being sent overseas, and she got to visit them several times.

“I suspect he would have been immensely proud to have been asked to contribute and to do his little part.”

John Grant's carving of a lyrebird and clematis and koala. It is two of 12 panels in the school hall at Villers-Bretonneux. Photo: Courtesy Amanda Wescombe

Écrire commentaire